Who was Frederick Augustus Hihn? He wasn't the founder of Santa Cruz County, but his power and influence in its early years means that he might as well have been. He didn't own the county, but a good portion of its land passed through his hands at one point or another. He wasn't the county's biggest or wealthiest lumberman, but that certainly didn't stop him from trying to be both. And he wasn't the county's most famous or popular politician, but in his time he was both famous and popular. No, Frederick Hihn was something different: he was a visionary, an entrepreneur, a philanthropist, and an everyman in almost every way. He was the quintessential Gilded Age gentleman. He appeared on the scene just as California was becoming a state and lingered into the second decade of the twentieth century. In many ways, Santa Cruz during the second half of the nineteenth century was Hihn's town, and everyone knew it.

|

| Frederick Augustus Hihn in stately repose, c. 1900. [California State Library] |

Friedrich August Ludewig Hühn was born on August 16, 1829, in Holzminden in the Duchy of Brunswick, at the time a part of the German Confederation but otherwise an independent duchy. His father was a merchant and he had six brothers and two sisters, some of whom will accompany Friedrich to the United States. For most of his early years, Hühn was expected to become a merchant, and most of his training in this time was toward that goal. In 1844, he graduated from the local gymnasium and began working for A. Hoffmann in Schöningen as an apprentice merchant. In 1847, he started his first business collecting medicinal herbs and preparing them for commercial sale. But Hühn was becoming dissatisfied with German politics and sought an escape.

|

| Hundreds of abandoned ships left by gold-seekers in Yerba Buena Bay, San Francisco, 1853. The Reform may well be one of these ships. [Smithsonian National Museum of American History] |

He began making plans to move to Wisconsin when gold was discovered in California. After much contemplation, Hühn finally decided that the best option for himself and his family was to head to California and search for gold. It was not an entirely selfish motivation that drove him, though—his family was not wealthy and Hühn wanted to provide for them and his parents so they could live more comfortably. He boarded the ship

Reform on April 20, 1849 and spent the next six months sailing around Cape Horn to San Francisco, where he arrived on October 12.

|

| Gold mining in Placer Ravine near Auburn, 1852. [Smithsonian] |

Hühn spent the next month preparing himself for the Gold County and purchasing a claim near the Feather River's south fork. But he did not anticipate the winter rains, which flooded his claim and washed most of his tools and supplies downriver. By December 1, 1849, Hühn was back in Sacramento without money or any practical ability to return to his claim. Giving up on the dream, he joined with a partner who had worked the claim with him, E. Kunitz, and opened a candy shop in downtown Sacramento. But disaster struck again on Christmas Day when the American River overflowed and destroyed their shop. Hühn decided to return to the gold mines and went to Long Ear near Auburn, where he finally had some success.

|

| Downtown San Francisco in 1851, showing several of the main businesses in town including a drug store left of center, although whether this was Hihn's is unknown. Photograph by Daniel Hagerman. [Fine Art America] |

|

Therese Paggen, c. 1870. [Hihn-Younger

Archives, University of California, Santa Cruz] |

It was while working near Auburn that Hühn finally decided to apply to become an American citizen on June 6, 1850. Casting off his German origins, he adopted the new name Frederick August Hihn. Shortly afterwards in August, he returned to Sacramento and became the manager of two hotels on K Street. But this venture proved too tedious for the ambitious Hihn and he moved back to San Francisco, where he opened his first mercantile store, a drug store on Washington Street. It was in San Francisco that he met Therese Paggen, a French immigrant, whom he married three years later on November 23, 1853.

Hihn did not thrive while living in San Francisco. His drug store burned down on May 5, 1851, and he immediately switched to selling mattresses. But his mattress stock caught fire and were destroyed on June 22. During this time, he also lost most of spare cash to theft and was at times living on friends' spare beds and couches. By June 30, Hihn had decided to return home, but a friend convinced him to get a job at the Sacramento Soap Factory. It was there that he met Henry Hintch, who convinced Hihn to relocated with him to Mission San Antonio to grow tobacco. They took a substantial load of supplies with them on muleback and discovered, to their surprise, how popular their items were with the local Californios when they stopped to rest for a night at San Juan Bautista. Within days, they had run out of supplies, so Hihn rode back to San Francisco to purchase more goods for sale.

|

| Therese Paggen, their first child Katherine Hihn, and Frederick, c. 1858. [Hihn-Younger Archives, UCSC] |

After make a few more sales, Hintch and Hihn rode on to San Antonio, but near Soledad the two decided to turn back and make for Santa Cruz instead in order to catch a ship bound for San Francisco. It was a fateful decision. The pair crossed the Pajaro River into Santa Cruz County on September 19, 1851, and Hihn never really left again. He purchased a home at the corner of Willow Street (Pacific Avenue) and Front Street and opened a mercantile shop in late 1852. His was one of the few local businesses to stay afloat during the terrible financial recession of the mid-1850s, and it meant he was in a good position to expand afterwards. It also meant he was finally financially secure enough to marry Therese Paggen.

|

| Frederick Hihn with his four grandchildren, c. 1900. [Hihn-Younger Archives, UCSC] |

|

Charles B. Younger, Jr., husband of Agnes Hihn,

who together with her helped preserve Hihn's legacy.

[Hihn-Younger Archive, UCSC] |

Hihn's family came along rather slowly, at least comparably to the time. He was twenty-four when he married Therese and she was only seventeen, which may explain the delay before their first child was born. Katherine Charlotte Hihn was born on September 8, 1856. She would later marry William Thomas Cope. Louis William Hihn was their second son, who married Harriet Israel and had two children. Their third child, Elizabeth, died at less than a year old, and this seemed to delay the couple from having more children until 1864, when August Charles Hihn was born. August married Grace E. Cooper but had no children. The most famous of the Hihn children was Frederick Otto, the fifth child, who married Minnie E. Chace and had one son, Frederick Day Hihn. Frederick and Therese had another son, Hugo, in 1869, but he also died young. The couple's penultimate child, Theresa, married George Henry Ready and had a daughter, Ruth Ready, who lived until 1988. But it was their final child, Agnes, who proved the most prolific. She married Charles Bruce Younger, Jr., the son of Frederick Hihn's lawyer, and they had three children, the youngest of whom, Jane, only died in 1999. It was the Younger family that ultimately donated much of Hihn's business and personal documents to the University of California, Santa Cruz, which forms the basis of the university's special collections archive.

Hihn officially became a citizen on July 2, 1855, and a strange story developed around the same time relating to his wealth. Around 1855, Hihn purchased a gold claim along Gold Gluch. This was in response to a large boulder that was found on the gulch that contained a large amount of gold. The rumor goes that Hihn sacrificed his wheat-grinder, that he had used extensively over the previous two years to grind wheat into flour, in order to grind the boulder down to dust, from which the gold could be extracted. Naturally, he received a portion of the gold in payment for both purchasing the claim and sacrificing his grain mill. While there is no evidence to the truth of this story, it does explain the fate of the gold-laden boulder, the disappearance of Hihn's flour industry, and his substantial fortune that somewhat suddenly appeared in the late 1850s. The truth of the matter will likely never be known for certain.

|

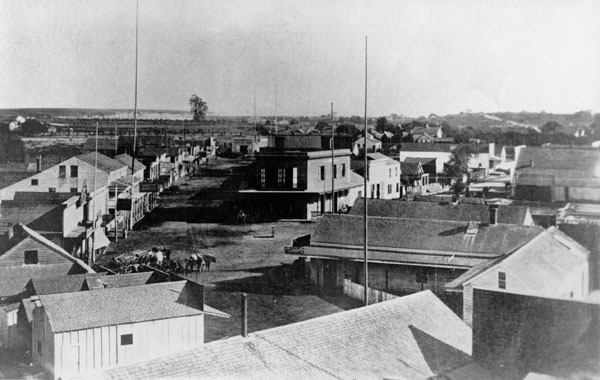

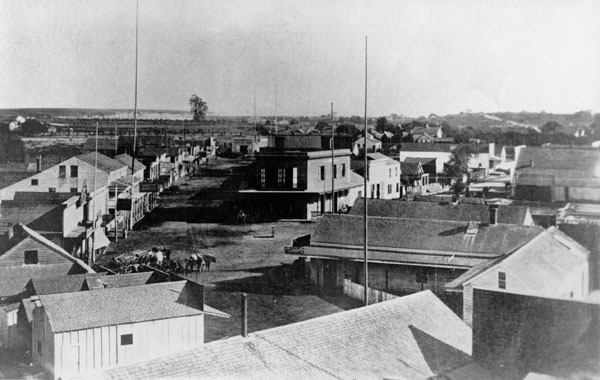

| The earliest-known photograph of downtown Santa Cruz, 1866. The brick-built flatiron building at the center of the photograph was built by Hugo Hihn in 1860 to house the mercantile store he purchased from his brother three years earlier. [Santa Cruz Public Libraries] |

Frederick Hihn entered the most significant stage of his life on August 21, 1855, when he purchased his first major property in Rancho Soquel Augmentacion through a court auction. Over the next five years, Hihn purchased several other tracts in Ranchos Soquel and Soquel Augmentacion. At this time, Hihn was also increasing his interest in business investing. In 1856, he joined Elihu Anthony in developing the Santa Cruz municipal water system. Tired of owing money and being in debt, he sold his mercantile business in December 1857 to his brother, Hugo, who had recently arrived in California with their brother, Lewis. Hugo rented the upstairs for use as city hall for four years while running his business downstairs. Hugo eventually sold the building and returned to Germany. In 1858, Frederick Hihn invested heavily in the Santa Clara Turnpike Company, a firm that passed through portions of his Rancho Soquel land on its way to the Summit.

|

| Hihn's majestic estate on Locust Street in downtown Santa Cruz. |

By 1861, Hihn was also looking into expanding a railroad into Santa Cruz County. In that year, he helped organize the San Lorenzo Valley Railroad, which ultimately hoped to build a railroad route into the Santa Clara Valley from Santa Cruz, but initially planned to connect Santa Cruz and the pioneer settlement emerging around Boulder Creek. It was probably for this cause that Hihn ran for and was elected onto the Santa Cruz County Board of Supervisors on September 4, 1861, beginning his term on May 5. He quickly discovered that the position did not provide him with all of the benefits that he sought, but he nonetheless was reelected in 1864. As his railroad plans languished in the courts over property rights, Hihn organized a second company, the California Coast Railroad, in 1867 with the goal of connecting Santa Cruz to Gilroy via a coastal route. Confusion spread by the Southern Pacific Railroad delayed this plan, and this delay likely led to him running and becoming a California State Assemblyman in 1871. Using his state-level influence, Hihn hoped to finally secure some funds to build a railroad in the county. But again, he was met with heavy opposition and did not run again in 1873. Shortly afterwards, he incorporated the Santa Cruz Railroad Company and became its president. This railroad was finally completed in 1876.

|

| Hotel Capitola on the beach at Camp Capitola, c. 1890. [Hihn-Younger Archives, UCSC] |

Much of Hihn's other public projects were linked to private ventures, generally housing subdivisions. Hihn founded Camp Capitola in 1869 on the beach at the mouth of Soquel Creek. On this land, he built a sprawling tent and cottage city and the massive Hotel Capitola. Up near the Summit, Hihn's Sulphur Springs was established along the turnpike to make commercial use of a hot spring found there. Hihn also was a key player in the founding of towns of Felton, Aptos, Valencia, Laurel, and the Fairview Park subdivision south of Capitola (all of the area south of Capitola Road and east of 41st Avenue to 49th Avenue). Further afield, he also helped layout the city of Paso Robles in 1899 and owned its famed El Paso de Robles Hot Springs Hotel.

|

| An oxen team working in Gold Gulch near Felton, 1898. [History San Jose] |

But the primary use Hihn had for his vast property holdings in Santa Cruz County was for harvesting lumber. When the South Pacific Coast Railroad began surveying its route into Santa Cruz County around 1877, Hihn tried to convince the company to run its line through Rancho Soquel. When this plan was rejected, he still managed to convince them to skirt the top of his property at Laurel, where a small lumber mill was established that cut timber for the railroad's tunnels and crossties. This mill operated on Hihn's land, but it was not his venture. The first mill that Hihn personally ran was on Trout Gulch in Aptos in 1883. It was a small operation able to cut 30,000 board feet of lumber per day, but the nearby timber was quickly exhausted.

|

| The Valencia apple barn, c. 1900, still standing in Aptos and home of Village Fair Antiques. [Aptos Museum] |

In 1884, a new mill was built three miles up Valencia Creek. This became Hihn's major base of operations. It could cut 40,000 board feet of lumber per day and ran for three years before burning down on November 29, 1886. Hihn rebuilt the next year with a larger 70,000 board foot capacity mill and constructed a narrow-gauge railroad line to it in order to make shuttling lumber to Aptos significantly easier. The mill shut down at the end of 1893 after almost completely clearcutting the Valencia Creek watershed. For the workers he left behind, he established an apple company and sold tracts of former timberland to his former employees to be used as orchards. Meanwhile, his lumber operations moved to Gold Gulch, then Laurel, King's Creek, and finally back to Laurel.

|

F. A. Hihn Company letter head showcasing various businesses that the company was involved in.

[Hihn-Younger Archives, UCSC] |

It was at this time that Frederick Hihn decided to retire and pass on the company to his family. He founded the F. A. Hihn Company in 1889 and officially retired from business at this time, although in reality he remained quite hands on for two more decades. During this time, he served as president of the Society of California Pioneers of Santa Cruz County, whose offices were in the upstairs of the Santa Cruz Southern Pacific depot. He helped to organize the Santa Cruz City Bank and the City Savings Bank of Santa Cruz. He served as a trustee of the Santa Cruz School District, and he also was president of the Santa Cruz Fair building Association. In 1902, he became one of the five founding trustees of the California State Polytechnic College, which became CalPoly San Luis Obispo. It was he who selected and arranged the purchase of the campus site and helped design and build the first structures, with help from local architect William Henry Weeks.

|

| Frederick Hihn with his daughter, Agnes, during a European vacation in 1893. [Hihn-Younger Archives, UCSC] |

By the late 1900s, age was finally having an impact on Frederick Hihn. He negotiated the sale of his commercial lumber business to the A. B. Hammond Lumber Company in March 1909, although the F. A. Hihn Company retained all properties and could continue to cut lumber, just not sell it to anyone other than Hammond. Hihn continued to be seen in town and participate to the best of his abilities until his death on August 23, 1913 at his home on Locust Street. He had just turned eighty-four years old. He was survived by several children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren, several of whom still live in Santa Cruz County today. In later years, his home served as city hall before eventually being demolished in the 1960s to build the current city hall.

Citations & Credits:

- Harrison, Edward S. History of Santa Cruz County, California. San Francisco: Pacific Press Publishing, 1892.

- Powell, Ronald G. The Frederick Hihn Story. Unpublished manuscript. University of California, Santa Cruz, c. 1992.

- Stevens, Stanley D. A Researcher's Digest on F. A. Hihn and his Santa Cruz Rail Road Company. Santa Cruz, CA: University Library, 1997.

- Whaley, Derek R. Santa Cruz Trains: Railroads of the Santa Cruz Mountains. Santa Cruz, CA, 2015.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.