Railroads did not appear in Santa Cruz County overnight. Between the first whisper of a local railroad published in the Santa Cruz Sentinel in December 1862 and the completion of the county's first railroad in October 1875, several plans were made and companies incorporated to build a railroad somewhere within the county. Without question, the most enthusiastic promotor of local railroad schemes was Frederick A. Hihn, whose wealth, vast land holdings, political influence, and general popularity afforded him much leverage in pursuing his grand vision for the county. Following a brief debate published in the Sentinel over several weeks in January 1866, Hihn pushed forward with his plan to build a standard-gauge railroad that would connect Santa Cruz County to the San Francisco & San José Railroad, which had opened January 16, 1864. Surveys were undertaken and public forums were held to compare the merits of a route to San Francisco via the San Lorenzo Valley—promoted by "Sayante" (probably Thomas S. Farmer)—versus a route along the coast and up the Pajaro Valley to San José. It took over a year for two rival companies to materialize. The San Lorenzo Railroad formed first on June 20, 1867. Two days later, on June 22, Hihn incorporated his own company with the aim of linking Watsonville to San José via Gilroy.

|

| Frederick A. Hihn wearing a Society of California Pioneers sash, 1880s. [University of California, Santa Cruz — colorized using DeOldify] |

California Coast Railroad Company (1867 – 1870)

The California Coast Railroad was financed by a great many members of Watsonville and Pajaro Valley society, including Nathaniel Chittenden, Charles Ford, Lucian Sanborn, and James Sargent. It was a bold but plausible plan with a moving target that hoped to connect with the nascent Southern Pacific Railroad wherever it was convenient. At the time, the exact plans for the Southern Pacific Railroad were unclear except that it hoped to construct a railroad south from San José through Gilroy. Two options from there were to continue down the San Benito Valley and cross into the San Joaquín Valley at the first opportunity. Alternatively, the route could turn down the Pajaro River and continue south via the Salinas River. Most surveyors at the time favored the former option, and indeed the Southern Pacific Railroad did initially attempt that before changing its mind and taking the Pajaro Valley route. In any case, that was in the future. Hihn and his colleagues wanted to ensure that they got their connection regardless of Southern Pacific's eventual decision.

|

| Sketch of Pajaro Landing, October 1856, by William Birch McMurtrie. [Bancroft] |

Surveys were conducted throughout late 1867 but little more progress was made and subscriptions were not actively solicited outside the initial backers. However, once construction of the Santa Clara & Pajaro Valley Railroad between San José and Gilroy began in February 1868, Hihn began selling stocks as widely as he could reasonably advertise them. His plan did not go as well as he had hoped. Trying to gather funds from the initial contributors was difficult enough, and the Pajaro Valley was not yet populated or wealthy enough to attract as heavy of an investment as was required. The stated capital stock was listed at the astronomical amount of $400,000 for only about 20 miles of relatively level track. Thus, the project languished even as the railroad to Gilroy was completed on April 10, 1869.

|

| A gathering of the Society of California Pioneers on Admission Day, 1880s. [Santa Cruz Public Libraries – colorized using DeOldify] |

Unperturbed, Hihn included the railroad into his autumn 1869 campaign for a seat in the California State Assembly. After winning the election, Hihn held several controversial and contentious public meetings. The result was a bill that would allow public funds to finance $8,000 per mile of the route, as well as branch lines up the San Lorenzo Valley (via the existing San Lorenzo Railroad Company) and Soquel Creek. Late during the drafting stage, the Southern Pacific Railroad incorporated the California Southern Railroad Company on January 22, 1870. This new railroad intended to build a route between Gilroy and Salinas and beyond—a total proposed length of 250 miles. In other words, it would follow the already-proposed route of the California Coast Railroad, and nobody in Santa Cruz County would have to finance it. As a result, Hihn inserted the California Southern into his railroad bill on March 5, 1870, and the California Coast Railroad was promptly forgotten.

|

| Stereograph of the Pacific Ocean House, 1866. Photo by Lawrence & Houseworth. [California State Library – colorized using DeOldify] |

Despite incorporation and the collapse of the earlier scheme, nothing happened for over a year. Southern Pacific resumed construction of its line south from Gilroy—nominally the Southern Pacific Railroad's mainline—but it stopped just outside Tres Pinos near Hollister. Hihn grew disappointed and began planning again. While his railroad bill had failed due to a veto from the governor, there was still public support for it and his plans. Thus, as his two years in the assembly were coming to an end, Hihn began an ambitious new plan to get the ball rolling once more concerning railroads in Santa Cruz County.

|

| San Francisco from the corner of California and Powell Streets, looking northeast, ca 1870. Photo by Lawrence & Houseworth. [Society of California Pioneers] |

Narrow Gauge Railroad Company (1870 – 1872)

Hihn's next scheme was not entirely his own. Part of the reason for the failure of his first plan was its extraordinary cost, which was simply beyond the financial ability of the county. But in 1870, the idea of narrow-gauge railroads invaded the Central Coast and inspired Hihn. With a narrower footprint, lower-grade rails and crossties, and tighter curves, narrow-gauge trains could be built at nearly half the cost of standard-gauge stock. Thus, when the Narrow Gauge Railroad Company was incorporated on November 15, 1870, Hihn made sure that he was one of its directors. The company was led by a British man, L. L. Robinson, and was managed from San Francisco. It had the lofty goal of building a narrow-gauge transcontinental railroad and as such had an initial $1,000,000 capital stock.

|

| Open fields near Half Moon Bay, 1880s. Photo by O. V. Lange. [California State Library] |

The company proposed as its initial route a narrow-gauge railroad down the coast from San Francisco through Santa Cruz County, with the trackage within Santa Cruz County the first to be constructed. However, the railroad was not alone in this goal—on March 23, the Southern Coast Railroad proposed a similar route. A week later, a third railroad, the San Francisco, Santa Cruz and Watsonville Railroad, also incorporated. Comparing all three, they appear to have been completely different firms with the latter two presumably standard gauge. None were promoted by the Southern Pacific Railroad and, notably, none ever succeeded in doing any more than surveying its proposed route. Surveyors for the Narrow Gauge Railroad passed through Santa Cruz County in May 1871 and were never heard from again, the project presumably failing not long afterwards. The only legacy the railroad may have left behind is its survey report, which was likely used by Hihn in later years to help plan the course of his later projects through the county. Undaunted, Hihn moved onto his next plan.

|

| Streograph showing the Santa Cruz Main Beach showing the Powder Works Wharf, 1866. Photo by Lawrence & Houseworth. [California State Library – colorized using DeOldify] |

San Lorenzo Valley Railroad Company (1871 – 1874)

Although initially reluctant to support a San Lorenzo Valley railroad scheme, he ended up adding it to his railroad bill in 1869–1870 as a way of drawing more support from the local community. The citizens of Santa Cruz in particular were supportive of it since it meant more revenue would pass through the town. It also would potentially put the Davis & Cowell lime company in its place, since the firm was aggressively blocking several smaller lime companies from getting their products to the wharves at the Santa Cruz Beach. Such was the reason why all progress on the earlier San Lorenzo Railroad had come to a halt. A lawsuit by Davis & Cowell had deprived the railroad of its funding due to legal fees and both firms were fighting a long battle in the courts to determine once and for all whether the railroad company could build a right-of-way through the lime company's lands without their permission.

Hihn waded into this fight assertively while still serving in the state assembly when he incorporated the San Lorenzo Valley Railroad Company on March 11, 1871. It was an opportunistic plan in that it hoped to draw on local demand for the route while inadvertently undermining the efforts of the company that had already formed for the purpose. As expected, the attempt did not succeed. Capitalized at $300,000, the board of directors was composed mostly of San Lorenzo Valley men but only one member of the old firm joined the group. The planned route was almost identical: sixteen miles up from Santa Cruz to Boulder Creek and beyond. The only substantial difference was that Hihn's proposed railroad would be narrow gauge, clearly taking inspiration from his earlier investment.

|

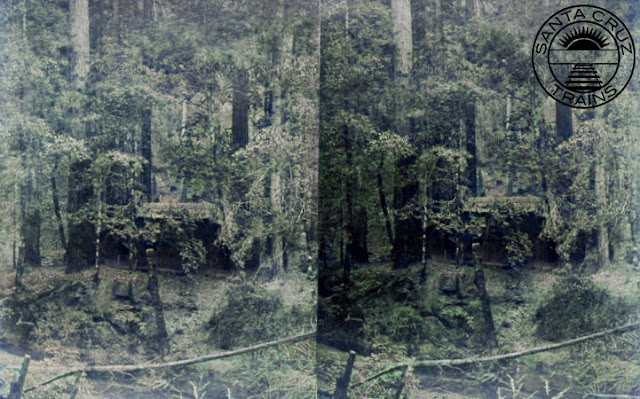

| Stereograph of a woodcutter in the Santa Cruz Mountains, ca 1877. Photo by J. D. Strong. [California State Library – colorized using DeOldify] |

Just like 1867, when the earlier company was formed, the Sentinel gushed about the plans, acting almost like the previous four years hadn't happened. It speculated that the route would eventually continue across the mountains to some point in the Bay Area. It discussed likely stops in the mountains, how popular the line would be with tourists, and how commuters could make a roundtrip journey to San Francisco in a day. Surveying for the new route began at the end of March 1871, suggesting that the partially-graded line of the San Lorenzo Railroad would not necessarily be used. Indeed, surveyors found a new short-cut under the Hogsback near the California Powder Works that could potentially reduce the route by 1.5 miles. The length of the proposed tunnel—1,100 feet—suggests that the line was still much closer to the San Lorenzo River than the route later taken by the Santa Cruz & Felton Railroad in 1874. The survey was completed at the end of April 1871. Efforts to associate the line with a proposed railroad in San José were ongoing.

|

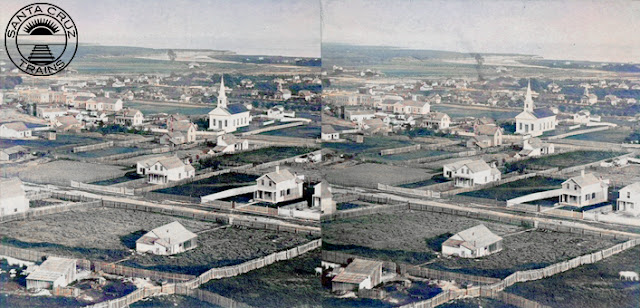

| Stereographic view of Santa Cruz, 1866. Photo by Lawrence & Houseworth. [California State Library – colorized using DeOldify] |

Speculation continued into 1872 but little more was done. The value of the company's stock remained stable and land speculators began clearing property in Boulder Creek at the proposed terminus of the railroad. Like with the San Lorenzo Railroad three years earlier, the idea of a railroad to Boulder Creek was enough to lead to the town's development. Nonetheless, when the San Lorenzo Railroad lost its case in the California Supreme Court on January 1, 1874, so too died the dreams of the San Lorenzo Valley Railroad. Both schemes were linked to the same idea: that a railroad could be built through Davis & Cowell's lands without its permission and without due compensation. When the case failed, all confidence in such a line collapsed and local investors pulled out. Hihn continued to act as chairman of the board but he may have lost interest in the project as early as August and was certainly looking at other options by early 1872. When the Santa Cruz & Felton Railroad formed in November 1874, it was financed entirely by outside investors who worked with Davis & Cowell to secure a right-of-way to its liking.

|

| Redwood trees in the Santa Cruz Mountains, ca 1874. Painting by John Ross Key. [Bancroft – colorized using DeOldify] |

San Jose & Santa Cruz Railroad Company (1871)

Hihn remained undaunted and began planning his next railroad scheme. Several investors in the Santa Clara Valley had continued to express interest in a route across the mountains and Hihn felt that it was time to push forward a plan he had promoted since September 1869: a railroad up the East Branch of Soquel Creek and down Los Gatos Creek. This route was of personal interest to him since he owned vast tracts of timberland at the headwaters of Soquel Creek and had struggled to economically harvest it since he had acquired it in the mid-1850s. Any route up Soquel Creek would be profitable to him, but he wanted to ensure he had a say in its construction. Thus, after four months of heavy speculation in newspapers and the completion of a survey of the route in May 1871, Hihn incorporated the San Jose & Santa Cruz Railroad Company on July 25, 1871.

|

| Soquel Landing in Capitola, 1870s. [Santa Cruz Public Libraries – colorized using DeOldify] |

The proposed narrow-gauge railroad would be 38 miles in length and run from Santa Cruz eastward to Capitola, where it would turn up Soquel Creek and snake along its East Branch until it found a reasonable location for a tunnel under the Summit to the headwaters of Los Gatos, probably near today's Lake Elsman. From there, it would more or less follow the route later built by the South Pacific Coast Railroad in 1878–1880, until the line arrived in San José. Capital stock was set at $500,000 and Hihn was appointed president.

|

| Capitola Beach, ca 1875. Photo by Romanzo E. Wood. [California State University, Chico – colorized using DeOldify] |

The nascent route was too little and too late. Indeed, why it was even incorporated is unclear since, on July 17—less than two weeks before—the Southern Pacific Railroad began construction on its long-delayed Watsonville Branch, which would initially extend from Gilroy to Pajaro or Watsonville, and eventually continue to Salinas. This branch line would partially resolve the stated reason for the San Jose & Santa Cruz Railroad since it would finally connect Santa Cruz County to the Santa Clara Valley by rail. While the task of linking Santa Cruz to the Monterey County line was still in the future, part of the decision had been taken away from Hihn and his investors pulled out. The Watsonville Branch was completed to Pajaro on November 26, 1871. Three years later, it was re-designated as the main trunk line of the Northern Division of the Southern Pacific Railroad after the former mainline to Tres Pinos was declared infeasible.

|

| Logging with oxen above Soquel, 1870s. [San Joaquin Valley Library System – colorized using DeOldify] |

Hihn's plans for a railroad along Soquel Creek, while possible from an engineering standpoint, was never built. He returned to the idea several times over the years, even reserving in 1889 a right-of-way through large sections of land he owned or purchased that still exists today under the name "Hihn Railroad Grade" on property maps. This route would likely have followed at least part of that surveyed in 1871. Hihn did eventually build a very small stretch of track at Laurel along the West Branch of Soquel Creek, but due to the steep grade from the South Pacific Coast Railway's right-of-way, it was only usable as part of an incline tramway.

|

| The offices of Charles Ford in Watsonville, 1890. Photo by George Menasco. [Watsonville Public Library] |

Santa Cruz & Watsonville Railroad Company (1872 – 1873)

The prospect of a railroad actually reaching Santa Cruz County from San Francisco (via the Santa Clara Valley) excited everyone and Hihn seized the moment once again. Abandoning all of his previous projects, he put his effort into organizing a standard-gauge railroad that could connect Santa Cruz with the Southern Pacific tracks at Pajaro. In mid-December 1871, a ballot measure passed by a heavy margin granting a subsidy to build a railroad between the two points. Only Watsonville residents resisted the measure because they already considered themselves connected to the Southern Pacific network and saw little advantage in supporting a railroad to Santa Cruz. Following a month of discussion and planning, on January 18, 1872, the Santa Cruz & Watsonville Railroad Company was incorporated.

The length of the route was set at 20 miles with it expected to follow the coastline closely. As with the previous two projects, Hihn was made president alongside several other local Santa Cruz entrepreneurs who had supported Hihn's previous schemes. Capital stock was set at the still optimistic $500,000, of which $100,000 was promised by the county at a rate of $5,000 per mile built. The county required construction to begin within six months and the entire line had to be completed by January 1874. On paper, everything seemed reasonable. Surveyors began their surveying and board members began soliciting subscribers.

|

| Portrait of Leland Stanford, 1870s. [Bancroft] |

It was in early April that Hihn made a fatal mistake. He met with Leland Stanford of the Southern Pacific Railroad in San Francisco, and during the meeting Stanford promised to conduct a survey in anticipation of taking over construction of the Santa Cruz & Watsonville Railroad. With such an important financier on board, the subscription drive collapsed. Why have locals pay for what the Southern Pacific would do itself? To complicate matters further, the Atlantic & Pacific Railroad sent surveyors into Santa Cruz County in June 1872 shortly after the incorporation of its subsidiary San Francisco & Atlantic Railroad. The company hoped to build a transcontinental route from San Francisco, from where it would follow the coast to Los Angeles before turning east to the Colorado River. That meant that two companies wanted to build standard-gauge railroads that would connect Santa Cruz to Watsonville—one by taking over the existing company, the other via an entirely new company with a grander vision. Both options seemed better than funding a railroad entirely on local funds and subscriptions.

|

| Streographic view of Santa Cruz from High Street, 1866. Photo by Lawrence & Houseworth [California State Library – colorized using DeOldify] |

And so ended Hihn's penultimate attempt to build a railroad. The public was distracted and in the summer of 1872, they felt confident that somebody else would solve their railroad problem for them. But they were wrong. By early September, it was clear that the Southern Pacific had both blocked the Atlantic & Pacific's plans in the Bay Area and reneged on its agreement with Hihn to take over the Santa Cruz & Watsonville Railroad. Faced with high costs and few funds, Hihn pitched the idea of a 40-mile-long narrow-gauge railroad between the San Mateo County line and Pajaro, thereby leaving open the possibility of a future take-over of the route. In late November, Hihn convinced a joint Santa Cruz–San Mateo County railroad committee to agreeing in principal to funding the line at a cost of $250,000.

|

| The Santa Cruz Railroad's Betsy Jane with its crew, ca 1875. [University of Southern California] |

An annoying delay caused by yet another appearance by Stanford in late January 1873 led to more empty promises, but this time Hihn was prepared. He asked for a show of good faith. Stanford surprisingly delivered and brought in surveying crews to map the entire proposed route to Santa Cruz. However, financial instability began rolling out of Europe in the summer of 1873 and the Southern Pacific Railroad was forced to pull out of its expansion plans throughout the state. Hihn pushed on and began gathering subscriptions. On August 4, 1873, he and a small group of associates incorporated the narrow-gauge Santa Cruz Railroad Company. This time, his scheme finally bore fruit and Santa Cruz entered the age of the iron horse. The rest is history.

Citations & Credits:

- Hamman, Rick. California Central Coast Railways. Second edition. Santa Cruz, CA: Otter B Books, 2002.

- Powell, Ronald G. The Reign of the Lumber Barons: Part Two of the History of Rancho Soquel Augmentation. Santa Cruz, CA: Zayante Publishing, 2021.

- Various articles, Santa Cruz Sentinel, 1866–1874.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.